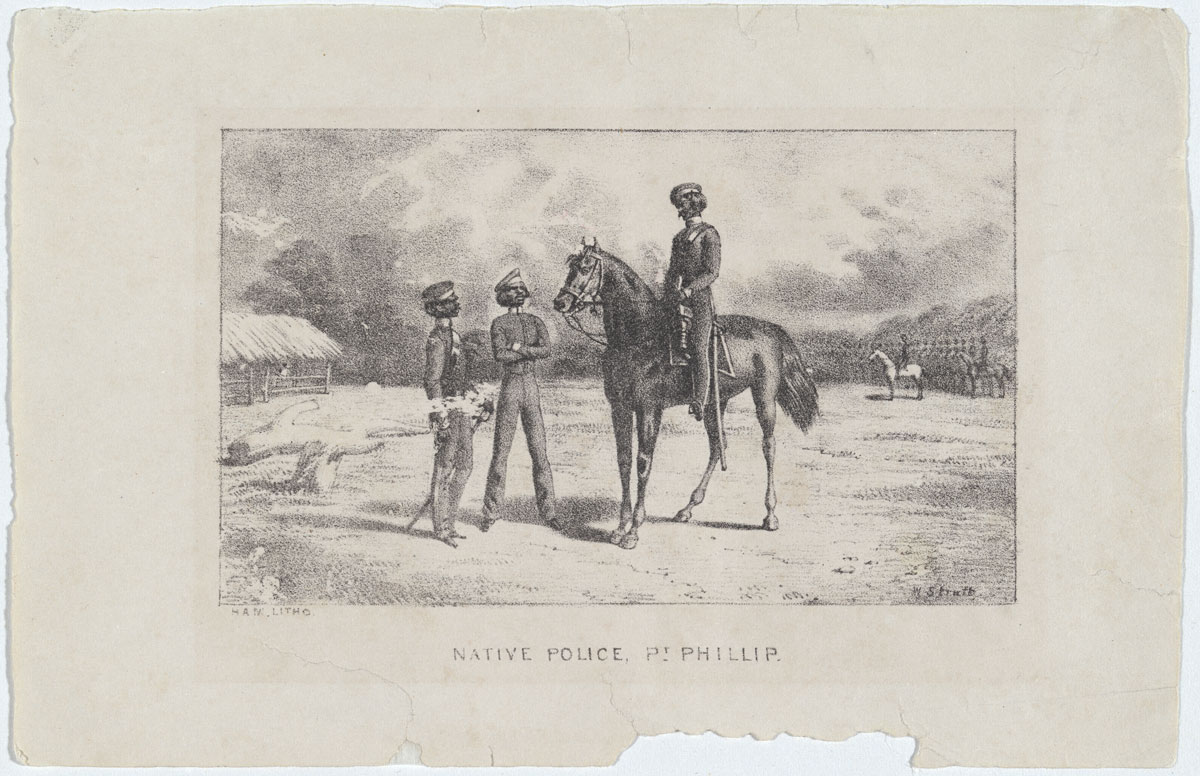

Native Police section of print publication must be accompanied by the following caption: William Strutt, print after Native Police, Pt. Phillip 1851 from The illustrated Australian Magazine (Melbourne: Ham Brothers, vol. 2, no.9, 1851) chalk-lithograph National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Purchased from Gallery admission charges 1989.

8. Native Police

The native police were initially stationed at the Police Paddock in Narre Warren, before being moved to the confluence of the Merri Creek and Yarra River in March 1842. The idea was to teach Wurundjeri men military discipline and English, so that they would come to see the benefits of “civilized society” and pass these qualities on to their families. Billibellary, Ngurungaeta (clan headman) of the Wurundjeri-willam, was enlisted to recruit other Wurundjeri men to join the police force. Although he sometimes wore his uniform at the camp, ‘he was too astute a diplomat to actually undertake active duty as a policeman.’[i] The native police were a powerful force in defeating the Aboriginal guerrilla resistance in outlying areas, although it is dubious as to whether the hard drinking British officers were the “civilising” influence that had been envisioned.

[i] Ellender and Christianson, People of the Merri Merri, 88

The concept of a Native Police force was first proposed by Captain Alexander Maconochie in 1837, as an alternative method to “protection” and based on ideas of assimilation and compensation for land.[i] Maconochie’s idea was that the members of the native police could be gradually educated in military discipline and English, and that they would come to see the benefits of “civilized society”, abandoning their “erratic” ways, and pass these qualities on to their families. The force was established in the Port Phillip District on three separate occasions – 1837, 1839 and 1842.

Billibellary, Ngurungaeta (clan headman) of the Wurundjeri-willam, was enlisted to recruit other Wurundjeri men to join the police force. Although he sometimes wore his uniform at the camp, ‘he was too astute a diplomat to actually undertake active duty as a policeman. As headman of the Wurundjeri-willam, he wanted to avoid a situation where he would be obliged to follow the direct orders of a British officer; neither was he prepared to risk his authority by exposing himself to the indignities involved in learning how to ride a horse.’[ii] The native police were initially stationed at the Police Paddock in Narre Warren, before being moved to the confluence of the Merri Creek and Yarra River in March 1842.

Machonochie’s hope that enlisted Aboriginal men would give up their traditional lifestyle did not go to plan. The men still participated in ritual combats, and left corps when out in the bush – something for which Thomas would withhold rations, leading to abuse against the protector by members of the force.[iii] Nor were the British officers the example of virtue that Machonochie envisioned when proposing the force as a civilizing influence. Alcohol was a particular problem. When asked by the Select Committee of the Legislative Council on the Aborigines in 1859 whether Thomas had found the men who had been troopers better conducted than others, he replied, ‘no, worse; and they are all dead’. Asked if they ‘had acquired a taste for dissipated habits?’, Thomas replied ‘yes, the most awful drunkenness.’[iv]

While the native police was not the “civilizing” force for the Wurundjeri and other Aboriginal people in and around Melbourne that was initially envisioned, Christie presents the argument that they were a powerful force in defeating the Aboriginal guerrilla resistance in outlying areas. The police force came to be feared by other Aboriginal people, while at least some in the European population viewed it as an expensive failure.[v]

[i] Ibid

[ii] Ellender and Christianson, People of the Merri Merri, 88

[iii] Ellender and Christiansen, People of the Merri Merri, 90

[iv] Report of the Select Committee of the Legislative Council on The Aborigines, 4

[v] Christie, Aborigines in Colonial Victoria, 71-72; Finn, The Chronicles of Early Melbourne, 56

The concept of a Native Police force was first proposed by Captain Alexander Maconochie in 1837, as an alternative method to “protection” and based on ideas of assimilation and compensation for land.[i] Maconochie’s idea was that the members of the native police could be gradually educated in military discipline and English, and that they would come to see the benefits of “civilized society”, abandoning their “erratic” ways, and pass these qualities on to their families. The force was established in the Port Phillip District on three separate occasions – 1837, 1839 and 1842.

Billibellary, Ngurungaeta (clan headman) of the Wurundjeri-willam, was enlisted to recruit other Wurundjeri men to join the police force. Although he sometimes wore his uniform at the camp, ‘he was too astute a diplomat to actually undertake active duty as a policeman. As headman of the Wurundjeri-willam, he wanted to avoid a situation where he would be obliged to follow the direct orders of a British officer; neither was he prepared to risk his authority by exposing himself to the indignities involved in learning how to ride a horse.’[ii] The native police were initially stationed at the Police Paddock in Narre Warren, before being moved to the confluence of the Merri Creek and Yarra River in March 1842.

Machonochie’s hope that enlisted Aboriginal men would give up their traditional lifestyle did not go to plan. The men still participated in ritual combats, and left corps when out in the bush – something for which Thomas would withhold rations, leading to abuse against the protector by members of the force.[iii] Nor were the British officers the example of virtue that Machonochie envisioned when proposing the force as a civilizing influence. Alcohol was a particular problem. When asked by the Select Committee of the Legislative Council on the Aborigines in 1859 whether Thomas had found the men who had been troopers better conducted than others, he replied, ‘no, worse; and they are all dead’. Asked if they ‘had acquired a taste for dissipated habits?’, Thomas replied ‘yes, the most awful drunkenness.’[iv]

While the native police was not the “civilizing” force for the Wurundjeri and other Aboriginal people in and around Melbourne that was initially envisioned, Christie presents the argument that they were a powerful force in defeating the Aboriginal guerrilla resistance in outlying areas. The police force came to be feared by other Aboriginal people, while at least some in the European population viewed it as an expensive failure.[v]

[i] Ibid

[ii] Ellender and Christianson, People of the Merri Merri, 88

[iii] Ellender and Christiansen, People of the Merri Merri, 90

[iv] Report of the Select Committee of the Legislative Council on The Aborigines, 4

[v] Christie, Aborigines in Colonial Victoria, 71-72; Finn, The Chronicles of Early Melbourne, 56

Native Police

Native Police section of print publication must be accompanied by the following caption: William Strutt, print after Native Police, Pt. Phillip 1851 from The illustrated Australian Magazine (Melbourne: Ham Brothers, vol. 2, no.9, 1851) chalk-lithograph National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Purchased from Gallery admission charges 1989.