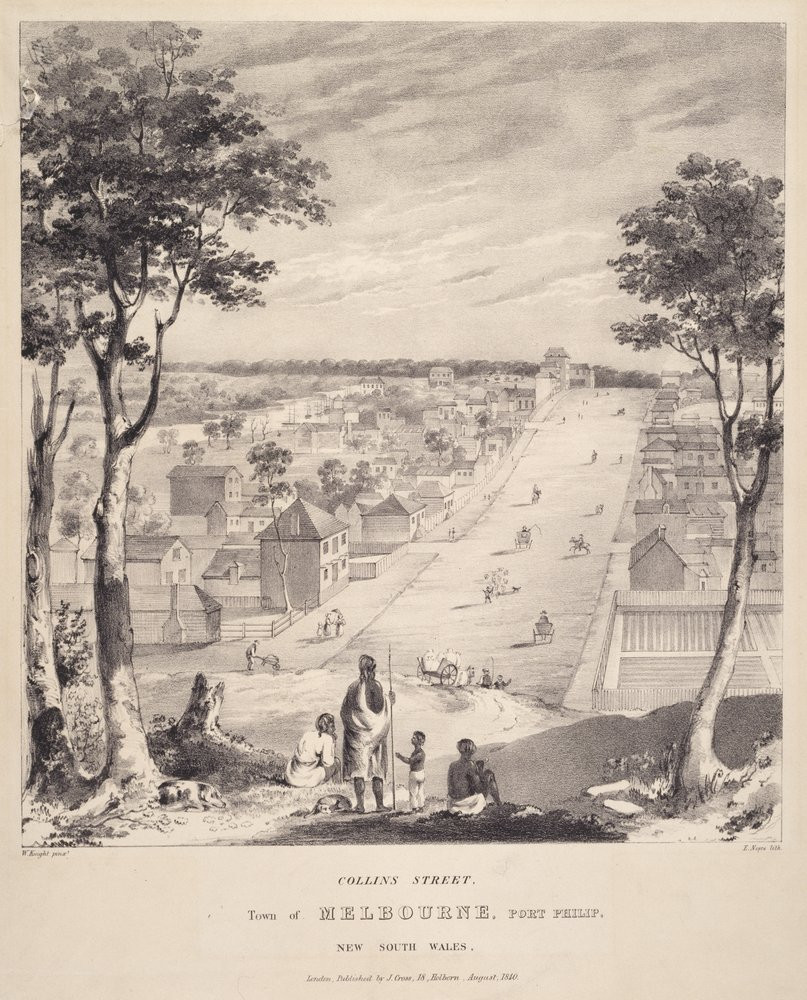

Collins Street - Town of Melbourne, Port Philip [sic], New South Wales, Elisha Noyce, picture collection, State Library of Victoria, Accession Number H24533

3. Dispossession

Wurundjeri dispossession of land took place through a variety of processes. Land was sold, bush was cleared for the creation of roads and buildings, and wetlands were drained. Over time, even the course of the Yarra River was changed. For the Wurundjeri, who had a spiritual connection to the land, these changes had a devastating impact on many aspects of their health and well being. The settlement was officially named Melbourne by Governor Bourke in March 1837.[i] The first land sales took place (without permission from the Wurundjeri) in Melbourne on 1 June, 1837. The following year, forty-one allotments of twenty-five acres each were sold in the areas that would become Collingwood and Fitzroy.

[i] A.G.L. Shaw, ‘Foundation and Early History’, in Andrew Brown-May and Shurlee Swain (eds), The Encyclopedia of Melbourne, online edition

Wurundjeri dispossession of land took place not just through displacement, but also through disconnection. Land was sold, bush was cleared for the creation of roads and buildings, and wetlands were drained. Over time, even the course of the Yarra River was changed. The disruption of sacred sites might be termed desecration. For the Wurundjeri, who had a spiritual connection to the land, these changes had a devastating impact on all aspects of their health and well being.

Prior to Melbourne’s settlement, European sealers and whalers had lived and worked along the Victorian coastline for decades, and the British had made attempts to establish settlements further out on Port Phillip Bay and Westernport Bay. The arrival of settlers during the 1830s was considered illegal under British law, but settlers came anyway, unable to resist the lure of prime pastoral land. The settlement grew through the early thirties and by the end of 1836, the British government conceded it couldn’t stop it. The settlement was officially named Melbourne by Governor Bourke in March 1837.[i] During the ceremony Bourke used William Buckley, an escaped convict who had lived with Watha wurrung people for thirty-two years, to tell the Aboriginal people present that he would be a friend as long as they were peaceable and obeyed the law.[ii]

As the settler population increased and the built environment developed, the European hold on the land was strengthened. The first land sales took place in Melbourne on 1 June, 1837. The following year, forty-one allotments of twenty-five acres each were sold in the areas that would become Collingwood and Fitzroy. It was intended that they would be paddocks.[iii] In the building boom of 1850, the allotments were subdivided and forest was cleared for firewood. The European population during this time rose from 600 people in 1841, to nearly 3000 people in 1850, and 3449 people in 1851.[iv]

Aboriginal people were pushed further and further out, and freedom of movement across the land became increasingly difficult. The settlers created new land boundaries with fences and often had guns to back them up. For the Wurundjeri, finding food within traditional clan boundaries became increasingly challenging. The settlers hunted wildlife on an unprecedented level, for sport as well as for food, reducing the amount that was available.[v] Introduced animals such as sheep and cattle trampled and killed vegetation that had been a staple of the Aboriginal diet.[vi] This sometimes forced Aboriginal people onto the land of other clans – a breach of protocol which sometimes led to inter-clan violence. Devastation from introduced diseases also influenced the willingness of Aboriginal people to return to former campsites, as happened at the confluence of the Yarra River and Merri Creek after the influenza epidemic of 1847.[vii]

The Wurundjeri-willam and other Aboriginal people of the Yarra and Melbourne area did not concede their land easily, but as the settlement grew and space to hunt and gather diminished, many of the dispossessed were eventually drawn to the settlement, where food and alcohol was available. As Melbourne developed into a town and then a city, there continued to be a strong Aboriginal presence in and around the settlement.

[i] A.G.L. Shaw, ‘Foundation and Early History’, in Andrew Brown-May and Shurlee Swain (eds), The Encyclopedia of Melbourne, online edition

[ii] Edmonds, Urbanizing Frontiers, 82

[iii] Bernard Barrett, The Inner Suburbs: The Evolution of an Industrial Area, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1971, 14

[iv] Ibid, 20; Shaw, ‘Foundation and Early History’

[v] Christie, Aborigines in Colonial Victoria, 42

[vi] Richard Broome, ‘Aboriginal Melbourne’, in Brown-May and Swain, The Encyclopedia of Melbourne

[vii] Clark and Kostanski, , ‘An Indigenous History of Stonnington’, 83-4

Wurundjeri dispossession of land took place not just through displacement, but also through disconnection. Land was sold, bush was cleared for the creation of roads and buildings, and wetlands were drained. Over time, even the course of the Yarra River was changed. The disruption of sacred sites might be termed desecration. For the Wurundjeri, who had a spiritual connection to the land, these changes had a devastating impact on all aspects of their health and well being.

Prior to Melbourne’s settlement, European sealers and whalers had lived and worked along the Victorian coastline for decades, and the British had made attempts to establish settlements further out on Port Phillip Bay and Westernport Bay. The arrival of settlers during the 1830s was considered illegal under British law, but settlers came anyway, unable to resist the lure of prime pastoral land. The settlement grew through the early thirties and by the end of 1836, the British government conceded it couldn’t stop it. The settlement was officially named Melbourne by Governor Bourke in March 1837.[i] During the ceremony Bourke used William Buckley, an escaped convict who had lived with Watha wurrung people for thirty-two years, to tell the Aboriginal people present that he would be a friend as long as they were peaceable and obeyed the law.[ii]

As the settler population increased and the built environment developed, the European hold on the land was strengthened. The first land sales took place in Melbourne on 1 June, 1837. The following year, forty-one allotments of twenty-five acres each were sold in the areas that would become Collingwood and Fitzroy. It was intended that they would be paddocks.[iii] In the building boom of 1850, the allotments were subdivided and forest was cleared for firewood. The European population during this time rose from 600 people in 1841, to nearly 3000 people in 1850, and 3449 people in 1851.[iv]

Aboriginal people were pushed further and further out, and freedom of movement across the land became increasingly difficult. The settlers created new land boundaries with fences and often had guns to back them up. For the Wurundjeri, finding food within traditional clan boundaries became increasingly challenging. The settlers hunted wildlife on an unprecedented level, for sport as well as for food, reducing the amount that was available.[v] Introduced animals such as sheep and cattle trampled and killed vegetation that had been a staple of the Aboriginal diet.[vi] This sometimes forced Aboriginal people onto the land of other clans – a breach of protocol which sometimes led to inter-clan violence. Devastation from introduced diseases also influenced the willingness of Aboriginal people to return to former campsites, as happened at the confluence of the Yarra River and Merri Creek after the influenza epidemic of 1847.[vii]

The Wurundjeri-willam and other Aboriginal people of the Yarra and Melbourne area did not concede their land easily, but as the settlement grew and space to hunt and gather diminished, many of the dispossessed were eventually drawn to the settlement, where food and alcohol was available. As Melbourne developed into a town and then a city, there continued to be a strong Aboriginal presence in and around the settlement.

[i] A.G.L. Shaw, ‘Foundation and Early History’, in Andrew Brown-May and Shurlee Swain (eds), The Encyclopedia of Melbourne, online edition

[ii] Edmonds, Urbanizing Frontiers, 82

[iii] Bernard Barrett, The Inner Suburbs: The Evolution of an Industrial Area, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1971, 14

[iv] Ibid, 20; Shaw, ‘Foundation and Early History’

[v] Christie, Aborigines in Colonial Victoria, 42

[vi] Richard Broome, ‘Aboriginal Melbourne’, in Brown-May and Swain, The Encyclopedia of Melbourne

[vii] Clark and Kostanski, , ‘An Indigenous History of Stonnington’, 83-4